So after the shit fest that is Gentleman Jack getting axed, I re-watched some episodes of Person of Interest, a cyberpunk procedural with a bonkers premise: the government has a secret surveillance system that spies on all of us. On the surface, Person Of Interest looks like your average CBS copaganda network production, which was why it was dismissed by most critics and didn’t receive any recognition during its runtime. But the show is brilliant on a meta-textual level precisely because it looks conventional. Its otherwise explicit anti-state rhetoric was cleverly smuggled onto a network notorious for valorizing the police. As show runners Jonathan Nolan (Christopher outsold!) and Greg Plageman note in an interview for Entertainment Weekly: “It is almost like we snuck in, in sheep’s clothing.”

Person of Interest is anything but sheep’s clothing. It premiered two years before the 2013 Snowden scandal - which happened halfway through Season 3 - but eerily predicted what he revealed to a tee. There is a government surveillance network watching us, trackers mining our data for advertisers, and everything we do leaves a permanent digital footprint. When Person of Interest aired, it was a show that seemed to wear a ridiculous tin foil hat. But this garden variety network procedural soon became a scathing and thrilling critique on how technology works at the behest of a corrupt system. Less talked about, however, is how Person of Interest also became one of the most profound meditations on the importance of redemption and second chances.

Person of Interest follows a reclusive hacker, Harold Finch (Michael Emerson), and a former CIA assassin, John Reese (Jim Caviezel), as they indulge in violent vigilante business all over New York City. Post-9/11, Finch created a powerful surveillance system - also known as The Machine - which could predict terrorist attacks before they happen. Events involving mass casualties were marked as “relevant” and sent to authorities. Crimes involving ordinary citizens were labeled as “irrelevant” and deleted from The Machine’s servers every midnight. Finch let his business partner and best friend, Nathan Ingram (Brett Cullen), publicly take the credit for building the machine while he comfortably hid in the shadows.

Finch and Ingram then sold The Machine to United States government for one dollar. This was a grave mistake, as intelligence agencies were soon assigned to kill everyone who knew about the system. They murdered Ingram too, but not before he had the chance to secretly build a backdoor to access the “irrelevant” list that Finch and Reese now use to save civilians. Finch managed to escape because no one even knew he existed. The state is rotten to the core, and has been trying for years to weaponize The Machine to target people whom they consider a threat to national security.

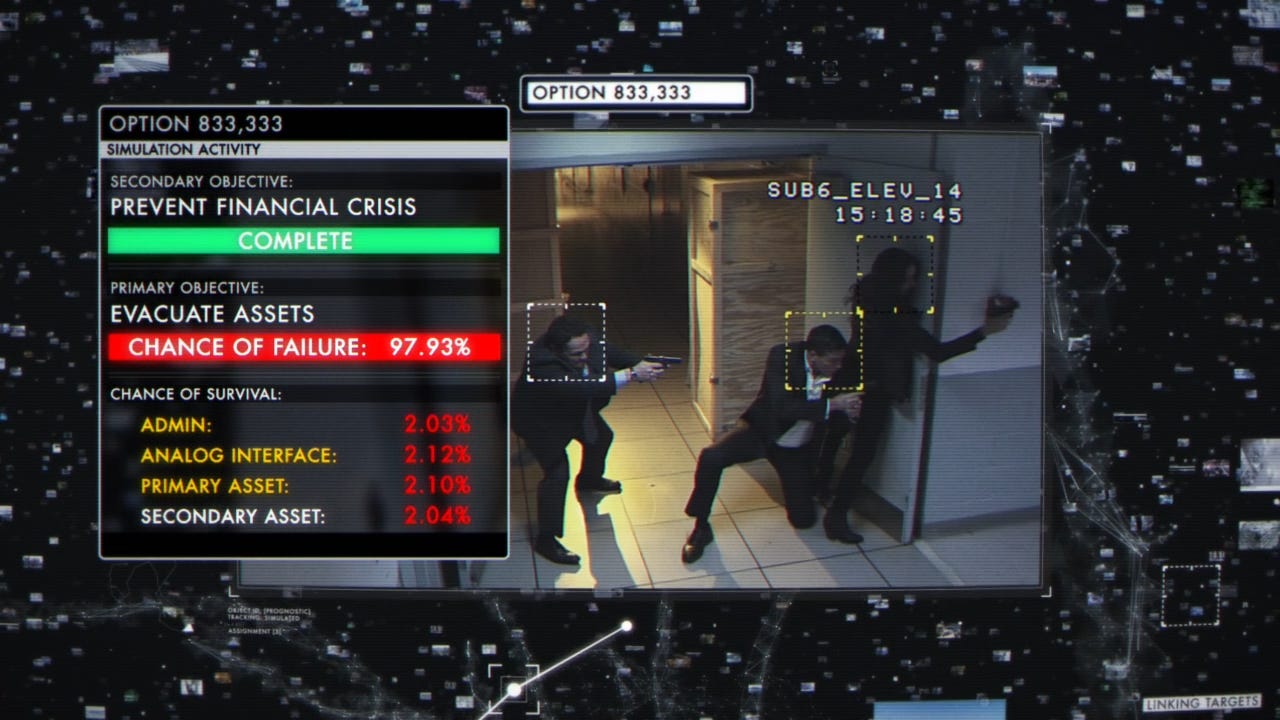

Luckily for Finch, the mark of his fundamental moral decency is that he had designed The Machine to be inaccessible to anyone — even to himself. All The Machine churns out is a social security number. There are no instructions given, and there is no way that anyone can use it to target people. Human beings have made mistakes with these numbers. Reese, for instance, was a CIA officer who was blindly led to kill people because of The Machine. But Person of Interest ultimately believes that our ability to make mistakes is also why we are capable of doing good. Free will is the only thing that separates human beings from machines. Herein lies the complicated ethical terrain which defines Person of Interest. Who deserves to be rescued? Who is more likely to be seen as terrorist? Can a computer decide who lives or who dies? Can any human being?

There is a darkness that belies Finch’s creation. A man who created God is just as likely to play God. Finch had downplayed the real consequences of building The Machine. Instead of a system which merely predicted events, Finch had inadvertently fathered a life - which, if set free, could bring about the apocalypse - and handed it over to the most corrupt people imaginable. Out of 43 versions of The Machine, some tried to kill Finch, others tried to kill civilians, and only one learnt to care. Wrecked with guilt, Finch is constantly haunted by a bleak world that he has had a hand in making. In many ways, Person of Interest is a show about seeking atonement.

In Season 2, Episode 11, The Machine gives Caleb Phipps’ (Luke Kleintank) “irrelevant” number to Finch. Caleb is either going to be a victim or a perpetrator of a crime. It is up to Finch to find out which is it. Cases are never black and white in Person of Interest. It turns out that Caleb is planning to take his own life, having been unable to cope with the death of his elder brother. Like Finch’s younger self, Caleb is a 17-year-old prodigy in computer science. Caleb’s mother is an alcoholic, and he sells drugs to pay for her addiction. He deliberately fails his exams because he has no desire to make a future when his life has been so cruel. It happens that Caleb is also working on a compression algorithm that will make billions when sold, and he plans to put all the money into a trust fund for his mother before he goes. Selling drugs isn’t the crime here. The crime is a system that is content with Caleb slipping through the cracks. No one cares about the Calebs of this world.

No one cared about young Finch too. Finch grew up with a father who was slowly losing his memory due to dementia. So Finch built a computer (with his bare hands) that could store his father’s memories for him. This first computer eventually became The Machine. The one version of The Machine which learnt to care did so because somewhere inside Finch’s propensity for darkness is a terrified boy who loved his father. It is precisely because nobody cares that Finch learns how important it is to care, even if it is just for one young boy he doesn’t know.

The kindness that Person of Interest has for people who are seen as irrelevant and expendable is abundant. Finch, who was forced to live most of his life in anonymity, will soon become relevant to Caleb, as he eventually talks the young teenager off the ledge by using π as a mathematical analogy to explain why his life matters.

CALEB: What’s the use? We are just gonna keep breaking things, over and over.

HAROLD: The thing about the world, is that it doesn’t have any extra pieces. It’s like π. It contains everything — you remove a single piece, no circle. Your recklessness, your mistakes … it is why when they say you can’t change the world, you won’t listen. The world is better off with both of us in it. If you think money can replace you, you haven’t seen the whole equation.

Finch’s speech is far from trite or cliche. Building The Machine led Finch to Caleb. Somewhere along the infinite string of numbers that makes up π, Finch and Caleb’s numbers met. If Caleb goes ahead with his plan, the circle will fall apart. Caleb tells Finch that all people do is break things. Human beings are bad code — a synonym for irrelevance — and are hence innately compelled towards cruelty. Finch believes otherwise. The choice to make mistakes demands the difficult choice to learn from them; people are worth saving because they can change. Atonement doesn’t exempt Finch from his sins, but it does mean that Caleb can be saved, at this exact moment, by a man who betrayed the world all those years ago. There is no machine or God, only people who are committed to doing good even when it is hard.

And so Caleb gets to grow up. A few years later after their fateful encounter, Caleb hands over his newly patented compression algorithm (unknowingly to save The Machine) to Finch without questions asked. People who are given second chances are likely to make a future for themselves and do good in return. But we cannot see the full equation if we consider certain lives to be irrelevant and refuse to put in the work into helping them.

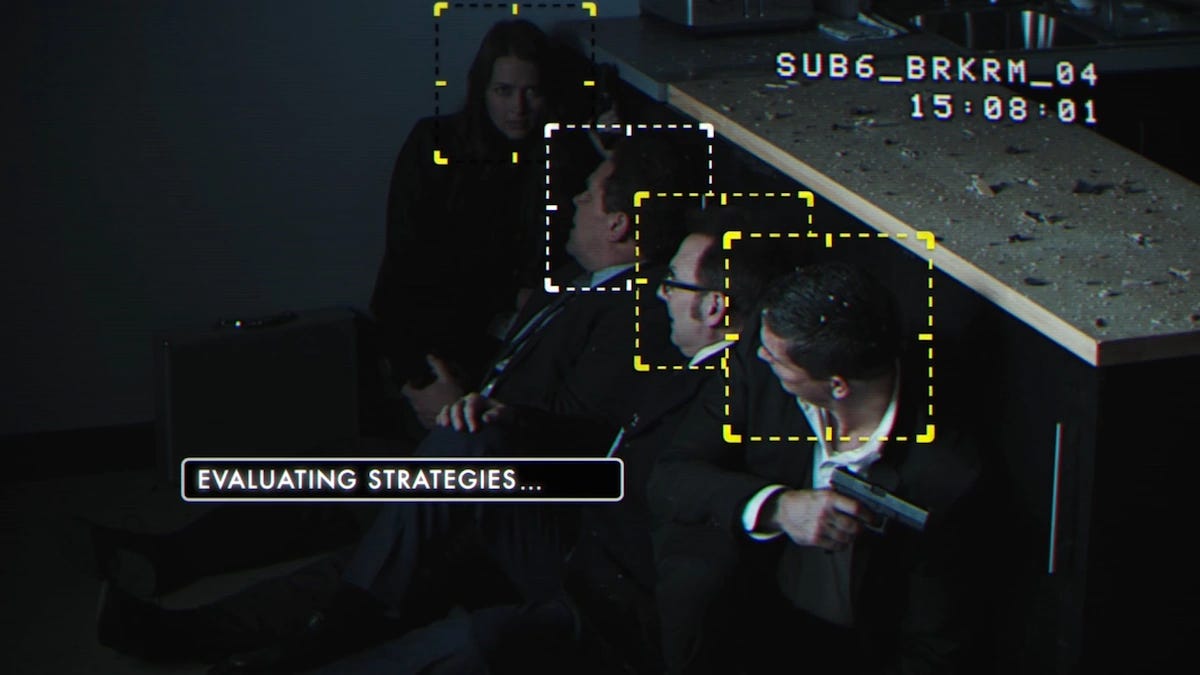

Person of Interest documents the dangerous emergence of artificial intelligence after the war on terror. It plainly states the moral rot inherent in American patriotism and refuses to shy away from the violence which makes up the surveillance state. Every episode features snippets of surveillance footage, and many have said that this gives the series a cold veneer. But beneath all those statistics is a warm and beating heart that fights extremely hard to believe in humanity’s goodness — even when there is so little of it left.

I came across this nicely phrase piece way too late. Now I'm thinking, with all coming and goings in the TV business who cares about a show which was on about ten years before, right? But to me, it's still fresh and speaks to heart. More so perhaps these days when I'm witnessing how AIs can easily and in reality fall into wrong hands.

But technology is not the only factor making this show memorable to me. It's about second chances and becoming a better person, no matter how far gone others might think you've been. There's always hope if there's a will.